Pathfinder International magazine was fortunate to interview former soldier and Chennai 6 member, Nick Dunn last year on his astonishing story of imprisonment in an Indian jail, an innocent set of men, locked up for seemingly no reason.

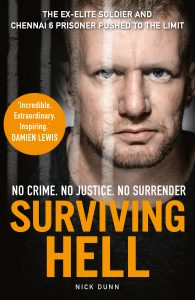

Since then, Nick has penned a book on his battle to be freed from his nightmare scenario. Publishers, Mirror Books sent us the first chapter to whet your appetite for a remarkable journey, none of us would want to encounter.

Read the Pathfinder interview with Nick from 2019 here.

Tuticorin District Principal Sessions Court, India 11th January 2016

How could this be happening? And how could it be happening to me?

That’s what I kept asking myself as this nightmare dragged on. I’m Nick Dunn, one of the Chennai Six. You’ve probably heard of us. We were British nationals banged up abroad because we were in the wrong place at the wrong time. As former soldiers, we were hired to protect shipping from modern-day pirates, but we were classed as mercenaries and treated like gun runners. We were not only innocent of any crime, there was no crime. From day one, the authorities in India had decided we were guilty, and that was that. They repeatedly ignored or overruled evidence proving our innocence. We were trapped in a third world country with a shockingly corrupt legal system and used as pawns by those who were out to make a name for themselves. What happened to us was a scandal, and news of our harsh treatment spread around the world.

Before this fateful day – 11 January 2016 – we had already spent more than two years either in jail or on bail, forbidden to leave the country while the case dragged on and on. Now here we were, back in front of a judge for a final resolution. I had been forced to scrape by, living off handouts from friends and family, army charities, and some of the many well-wishers from the UK who had been following our case in a state of constant astonishment. They were left wondering how we could be treated so poorly by a supposedly friendly nation in the 21st century. The conditions during our extended, forced stay in Chennai – the capital city of Tamil Nadu and formerly known as Madras – were appalling. The heat didn’t help. It was one of the hottest places in India where temperatures could regularly reach 35C or even higher.

We were finally about to have our day in court following a trial that had lasted four long months. At last, the judge was going to give his verdict. Surely, common sense and justice would win out, and we would be released. After all, we had done nothing wrong. Anyone with any sense could see that, couldn’t they? I wasn’t so sure. My experience up till now had led me to believe anything was possible in India. That was particularly true of Tamil Nadu, the worst state in the country, where we had been imprisoned. The level of corruption was unbelievable. I had seen it all at first hand and experienced the snail’s pace at which a case like ours could progress.

As I walked into the court that morning, I was almost late for the verdict thanks to the demands of reporters who were all desperate to get a few words from one of the infamous Chennai Six. They wanted to know how I was feeling and whether I thought our ordeal would soon be over. I was amazed by how many people had been following our story and, if nothing else, that gave me cause for optimism. There was a huge groundswell of support for our release. I told the reporters I was hopeful we might finally get justice, but I was under no illusions. I might have been a little delayed, but I wasn’t going to give my persecutors the satisfaction of letting them see me run, sweating, into court. Instead, I walked in with my head held high. I was experiencing a combination of nerves and excitement at the prospect of finally being released – along with a nagging dread that this still might not go our way.

Back at home in Ashington, 15 miles north of Newcastle, my sister Lisa, who had campaigned tirelessly for our release, was waiting for my phone call to let her know if we would be freed. My mam, who was in very poor health, and my dad were standing by too, both fretting about the outcome. My family had suffered. Their lives had been put on hold, their days filled with worry for me while I was banged up in a notorious, third world prison, full of murderers and rapists. I might not have done anything to deserve my imprisonment, but that didn’t stop the guilt I felt for the damage my ordeal was inflicting on my family. I knew I had to get out of here, for them as much as for me, and I had to do it quickly. I prayed it would be today. I stood at the back of the court room behind a wooden railing and alongside the men who had become my makeshift, dysfunctional family.

We faced the judge, the one man with the power to end this nightmare, if only he could show us some mercy. The judge was in his 60s. He was slouched in his chair and peered at us through his glasses, his receding hair partially covered by his ceremonial wig. He looked totally uninterested in us or the case. There was no jury, so what happened now was entirely down to him. In total, the Indian authorities had arrested and detained 35 men from our ship, including 12 crew and 23 former servicemen. We were on board to guard vessels from attack by notorious Somali pirates. These seaborne raiders had been making worldwide headlines – and a lot of money – storming ships, taking crews prisoner at gunpoint, then ransoming everyone and everything back to their owners and employers, sometimes for millions of dollars.

In the dock with me were 14 Estonians, three Ukrainians and 12 Indians. The rest were from the UK. Us Brits had become widely known as the Chennai Six. Our stories had been written about extensively, not just in the UK but all over the world. Nicholas Simpson was from Catterick; Paul Towers, Pocklington in East Yorkshire; Billy Irving came from Connel in Argyll; Ray Tindall from Chester; and John Armstrong was a Wigton man from Cumbria.

We were thrown together as part of the security force on the MV Seaman Guard Ohio and, for better or worse, we were all in this together. The outcome, good or bad, would be the same for us all. From where we were standing at the back of the court, we couldn’t follow the proceedings because the lawyers from both sides had their backs to us and were facing the judge. But, even if we could have heard what was being said, it would have meant nothing. Every word spoken in that court was in Tamil, and none of it translated for our benefit. It was a farce. They were discussing among themselves whether we were innocent or guilty and what should happen to us. Our lives were in their hands, but we couldn’t understand a bloody word of it.

The temperature was over 30C that day and we weren’t even allowed to sit down. Instead, we stood for hours, all day if that was necessary, while the lawyers argued, and the uninterested judge supposedly deliberated. I don’t remember there being fans on the ceiling but, if there were any, they were as much use as t**s on a fish for all the good they did. We were all sweating. The a***holes had even tried to take my bottle of water from me. I told them where to go. I needed something to fight the dehydration. Ahead of us was a room full of tables and chairs, with the defence team to our right and the prosecution on our left. The judge was on his raised platform, dressed in his robes, his minions around him. A stenographer was taking notes of everything that was said. The Indian legal system was based on the British model, but no reporters were allowed in the court room, and there were no friends or relatives of the accused in the public gallery. The only friendly faces inside the court were a couple of lasses from the British Consulate, Sharon D’Sylva and Manisha Hariharan. They were doing their best to help us because they knew we had done nothing wrong.

Compare our predicament to TV programmes like Banged Up Abroad, which tell the stories of young people who have committed crimes on foreign territories, many involving drugs. These people were often handed down long prison sentences and ended up filled with regret and bitterness because of their stupidity. Their one consolation was their guilt. They deserved their punishment, and they knew it. I hadn’t done anything. I didn’t deserve this. The police and prosecution had said the ship we were on board, the MV Seaman Guard Ohio, was trespassing in Indian territorial waters when it was intercepted. It wasn’t. Our ship had been moved towards the east coast to meet up with smaller boats supplying us with fuel, and to avoid the aftermath of Cyclone Phailin. Under maritime law, such an act of self-protection was permitted, particularly when there was no intention of heading into port. The coastguards lacked the equipment to pinpoint our actual position and, in court, they were never able to state accurately where we were. The police also said that six of the weapons we were carrying weren’t licensed. They were – and we had the certification to prove it. They doubled down on the claim by calling them illegal, automatic rifles, capable of rapid fire. Our ballistics expert proved in court the police were just plain wrong. Our expert told the judge that these half-dozen Heckler and Koch G3 battle rifles had been adapted to prevent them from ever firing as automatics. The judge said this key evidence had been duly noted, and we hoped that would be enough to secure an acquittal.

Our lawyers were from the firm of Anand, Samy & Dhruva, and our defence team was led by a Mr Muthusamy. I never did catch his first name but, like the rest of our small team of lawyers, he was optimistic. Our lawyers told me they had done everything they could, the trial had gone well, and they were convinced everything was looking good. I don’t know how many hours we were standing behind the rail that day waiting for the case to come to a conclusion. Outside it was growing dark. Eventually, the arguing between both sets of lawyers came to a halt, there was a recess for lunch, and we were left to dwell on our fate.

An hour later, we were called back into court to hear the verdict from the judge. Our first suspicion that the ruling had not gone our way came when extra police poured into the courtroom. More than 30 uniformed officers filed in and took up stations around us, blocking all the exits. I remember thinking, if they thought we’d be happy with the verdict, why would they send in reinforcements?

The judge made his final pronouncement in Tamil. We were none the wiser. People started drifting away from the court and we still didn’t know our fate. It was ridiculous. One of our lawyers approached. The look on his face told me something was very wrong, and I started to get a very bad feeling.

I’m a former Para who has been in combat in two war zones and narrowly avoided death, but I have never seen a man look as terrified as he did in that moment. He was approaching a group of very big guys with very bad news, and we could tell he wanted to be anywhere else but here. We were all desperate to know what had happened. When we did finally hear the verdict, we were left reeling.

“Gentlemen, it is not a good decision,” he said. “They have sentenced you to five years’ imprisonment on weapons charges.”

Eh? What? You’re f***ing joking? I was stunned. The news hit me like a blow. All the guys around me took the verdict the same way. They looked like I felt. Appalled and disbelieving. Despite our pessimism throughout, we had all still hoped that the Indian court might finally want justice to be done. Instead, this.

Five long years. I felt sick. In the seconds that followed, I began to absorb the terrible reality of my situation. Despite everything we had been told, I was not going to be freed. After six months in jail, followed by more than a year without even being charged, I was about to be put behind bars for a crime I did not commit. And five years! This wasn’t just a slap on the wrists from an Indian state looking to teach some foreigners a quick lesson. No, this was long, hard prison time in a hell-hole.

Five years!

At that point, I couldn’t take in any more. It was too much. I had forced myself to keep going all this time because I had always hoped and believed that, one day, the people in charge of this crazy legal system would finally see sense and we would be released. Now those hopes had been cruelly crushed and, in that moment, I had no idea how I would find the strength to carry on. One thing I did know – my nightmare was very far from over.

It was only just beginning.

To order a copy of “Surviving Hell” click here.

Image credit: Barry Marsden.