Louis Rudd MBE is a record-breaking polar adventurer, expedition leader, former Royal Marine Commando and SAS soldier, with 34 years of service. He is the first – and only – person to have traversed Antarctica twice using human power alone and has reached the South Pole three times from different coastal start points.

Louis’ first trip to Antarctica was in 2011/12 on the Scott-Amundsen Centenary Race Expedition. Along with Lt Col Henry Worsley MBE, Polar Medal, he skied 800 miles over 67 days unsupported from the Bay of Whales, up the Axel Heiberg Glacier to the South Pole, following the original route of the Norwegian Roald Amundsen. The expedition raised £150,000 for the Royal British Legion charity.

In 2016/17 he planned and led a team of five Army Reservists on a 67-day, 1,100-mile traverse of Antarctica. The SPEAR17 Expedition started at Hercules Inlet, skied 700 miles unsupported to the South Pole, collected a resupply and then crossed the Titan Dome and descended the Shackleton Glacier before arriving on the Ross Ice Shelf. The expedition won multiple awards including the Sun Military Award (Millie) for ‘Inspiring Others’ and in 2018 Louis was awarded an MBE for his leadership on the journey. The team raised £50,000 for ABF The Soldiers’ Charity.

In May 2018 Louis guided a team of five civilian friends on a 570km west-to-east traverse of the Greenland Ice Sheet. Despite a difficult season and hurricane-strength winds, the team completed the crossing in 27 days.

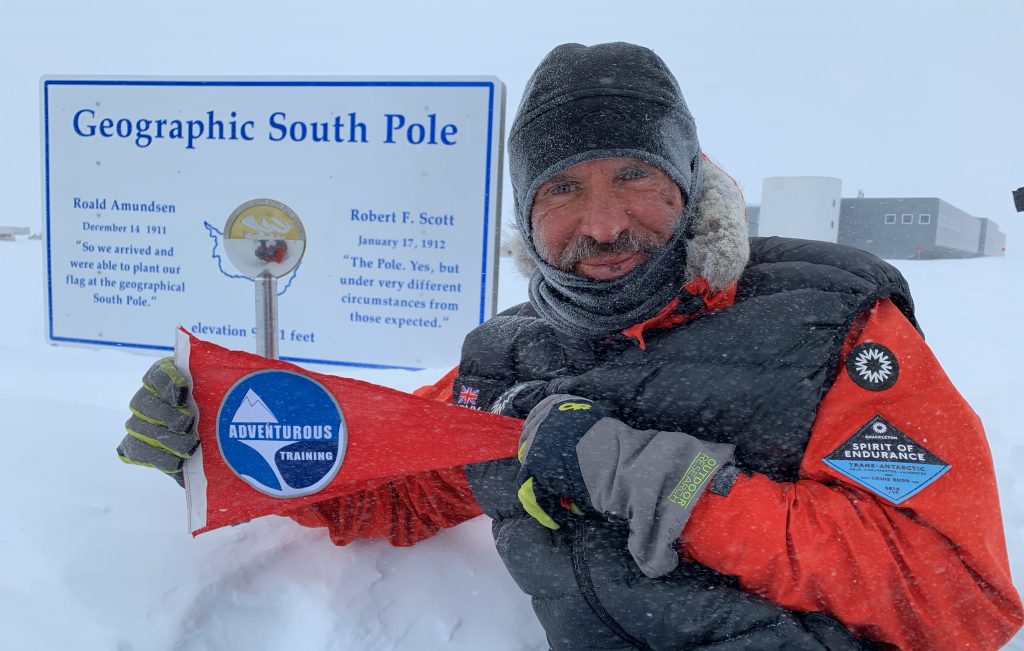

In 2018/19 he undertook the ‘Spirit of Endurance’ expedition which was a 56-day, 920-mile solo unsupported (no kites or resupply) crossing of the Antarctic continental land mass, becoming the first Briton and second ever in the world to complete this journey. He is the first person to traverse Antarctica twice on foot. Post-expedition, he completed a 5-month schools programme on behalf of the Army, lecturing on his military career and life of adventure. He was honoured to receive the Scientific Exploration Society’s ‘Explorer of the Year 2019’ award.

Military Muscle is naturally delighted then to have an exclusive interview with Louis, chatting about his military career, his Polar exploits, his resettlement from the forces and his new book entitled “Endurance”.

I left the forces on March 30 this year, so quite recent” begins Louis.

“I was lucky, towards the end of my time in the forces I started working for one of my sponsors and partners for one of my previous expeditions which is a company in London called Shackleton which was a very appropriate name. They are a clothing brand who make outdoor performance wear. They want to expand their business and start offering things like polar experiences so I transitioned across to start working for them as Director of Expeditions so I have been fortunate really to move into a job so things have been going pretty well.”

Tell us a little about your military career…

“From quite a young age I was interested in joining the forces and I saw it as a route to adventure. As a young lad, I read a lot of adventure style books, the likes of Ranulph Fiennes and I remember reading about Captain Scott and all that kind of stuff.

And then my mother remarried and my step father had been in the Marines several years before and that was my priority on joining the forces was being involved in adventure based stuff and so I joined the Marines at 16, straight out of school. I served 6 years with the Marines and then in 1992 when I was 22 years old, I did selection for 22 SAS, again I saw that as a great opportunity for a young Marine as my best chance of getting on adventurous operations and I served 25 years at Hereford and I was fortunate to have a fantastic career there.

It was during my time at Hereford that I ended up doing the Polar expeditions and I finished off my time, I was RSM of one of the three SAS units and then I took a commission as LE commission for three years as a Captain, but I kind of realised that a lot of LE jobs are office based, more so running stuff than delivering, so I felt after 35 years’ service that it was the right time to finish and try something a bit different.”

And how did that decision feel?

“Military life is all I had ever done, leaving school at 16 and going straight in and so all I have ever known is being a soldier and so I did think that I really need to focus on this transition period it is going to be a big change for me having been in so long, so I made sure I thought things through and did a lot of research and basically got fully prepared to minimise the disruption in the transition process.

It was a couple of years before (I started resettlement) that I decided that I am going to call it a day in the military at some point and I needed to think about what is it that I want to do? I looked at it and thought at my age having turned 50 at that point, I was like, I want to do something now that I really enjoy and that was the priority rather than try and go out and make loads of money. The priority was what am I actually going to be doing as a job to enjoy and everything else kind was kind of second place.

I thought about what do I want to do? What do I enjoy doing and what are my strengths and focussed on that. I really enjoy expeditions, I get a lot of satisfaction out of training other people, taking people on expeditions and watching them develop and get a real sense of achievement watching them overcome challenges, I find that really rewarding. All of these things were coming out when thinking about what I wanted to do and of course it had to bring in some kind of income and I had been working with Shackleton on my last expedition as an expedition partner and we had the initial discussions and laid out what I would like to do and asked if this would be a good fit for them and it was and it was a match made in heaven really.

I wore some of their clothing on my previous trip to get their brand out there and so they did a lot for me in support of the trip and I’d like to think they got a huge amount out of it in return. When I got back I mentioned leaving the military and they wanted to offer their clients the opportunity to use the clothing in the environment it is designed for, the Polar environment and we going to launch the new projects next year.”

Just how much work goes into planning an expedition?

“It depends on the scale. All of the three big Polar ones in Antarctica they were all Army adventure training expeditions and I couldn’t have done them without the support of the Army. So I need to highlight that the Army Adventure Training Scheme is phenomenal and there is actually a lot of resettlement benefit in this and the great thing about the Army Adventure Training Scheme is that you get the qualifications from the experience. You have the whole range of adventure style activities – kayaking, rock climbing, skiing, mountain biking, whatever it may be. You can progress through this scheme and get different levels of qualifications and disciplines and so if it is an outdoor activity type thing people are looking to do when leaving the military then use that adventure training scheme before you leave and get as many quals as you can.

I had done other lower level adventure training stuff in the past which have all been great fun, but these (the Polar expeditions) were level 3 projects and they involved a lot more work behind the scenes and on average for each trip probably about 2 years work. This included planning, preparation, the biggest challenge to these major trips in Antarctica is costs. The Army can’t be seen to be using (and rightly so) taxpayers money to fund these major trips so the Army support you in the fact that you are on duty, you are getting paid a salary whilst you are on these trips and you have got that insurance and top cover if things do go wrong, but ultimately you have to raise the funds yourself through corporate sponsorship.

Saying that though, the Army can assist you with that and you have lots of companies that support the MOD who can help.

In answer to your question though it is mainly 2-year projects of planning, fundraising, training, and preparing for the trips, selecting, and training your team, giving them all the necessary experience and skill sets and more.

I was serving as RSM with one of the SF Reserve units and as I got there as my two year tenure as RSM and I thought I need to do something for this unit while I am here and the Reserves in general and so I came up with the concept of a major flagship Army Reserves expedition to Antarctica. It had never been done before and again through Army Adventure Training Group I advertised and opened it up to anyone from across the Reserves for the five available places and I had literally hundreds of people apply!

We went through the briefing day and the realities of what the challenge was and I didn’t hold back, explained it is pretty brutal and basically I was going to run a yearlong selection process, which they had to commit to. It was going to be on weekends which were basically Polar boot camps. I had these big Land Rover tyres and they had to drag them around a 3 kilometre circuit and I would have them drag them around for 7 or 8 hours a day as well as conduct interviews and lots of other things thrown in there, just to give them a taste of what this type of journey can involve. In the end we had the right five people, went off to Norway and Iceland where we did the initial cold weather training.

Everyone involved in the process got lots out of it, even people that didn’t go, there were plenty of roles for people in support capacities and others got the trip out to Norway and that kind of stuff, all learning huge amounts about Polar travel, history and Antarctica and so I think it was beneficial for a lot of people.”

And so, what personally motivates Louis Rudd?

“I think always doing things like this for a good cause is a key motivator. I am becoming an ambassador for ABF Soldier Charity and throughout the course of those three Polar trips, I kind of raised over £200,000. That always motivates me when I am on the trip. Particularly on the solo one, there are obviously some pretty difficult days when you do feel sorry for yourself trudging along in a howling blizzard and it really helped to think “look you are here fundraising to support people that are actually in a much worse situation”. People have got a lifetime of challenge ahead of them with life changing injuries and that kind of helped keep things in perspective for me. Yeah, I am having a hard time now, but this is going to come to an end at some point, stop feeling sorry for yourself and get on with it!

In a more general sense before any major project, I always set out what my key aims and objectives were, the key messages for that trip. I limit it to four or five things, and I say this is why I am doing this trip. For example one would be “fundraising for a good cause”, or “doing it for a world first – flying the flag for Britain” other motivators would include stuff like we were doing some valuable medical research that was going to help weight loss and cancer patients so that was a huge motivator and I was also doing it as a tribute to a friend who lost his life in Antarctica and again another huge motivator so in any project you set out your stall before you embark on it. If anyone ever comes to you ask why, then straight away you have those key messages. If I am having a difficult phase on the trip, I will go right back to the start and just remind myself why I am doing this and I find that really helps clear things and restore that sense of purpose to what you are doing.”

And has there been any particular stand out points where it got really bad on the expeditions?

“On the solo one there were a couple of examples really difficult incidents.

I had a bit of a fall, I was skiing about half way to the South Pole and I was skiing in an area of disturbed ice, there were these huge ridges of ice called Sastrugi, they are carved by the wind and they are rock hard ridges and they vary from a few inches high to sometimes a few feet and I was in and amongst this area of Sastrugi and I was just stumbling over it on my skis, the pulp which was the big sledge behind you which was tied to your waist on a bit of rope was getting snagged and tipping over, really hampering my progress.

It was really bad visibility, so the cloud would come in and obscure the sun and you get this condition called Whiteout and you can’t see your hand in front of your face, it is really weird. You basically can’t see the difference from the ground to the sky and you can’t see the terrain you are skiing over.

And so I was stumbling through this Sastrugi and I ended up on a bit of a block of it, a bit higher up in the air than my surroundings and as I got to the end of it there was a sheer cliff face and a thing called a Wind Scoop, where the wind again kind of dug out the ground and resulted in this eight foot drop. It was only eight feet, but I just couldn’t see it and I skied straight off the end of it and face planted into rock hard ice below. (Louis laughs)

I crash landed and for a split second, I thought I was going down a crevasse which could have been a quite serious situation. And so, I face planted when I landed and then the sledge came over afterwards and landed across the back of my legs which was weighing about 90kgs, so this body slammed into me. I just lay there face down in the snow, bust my lip. I thought initially that I had broken my leg or something and that was quite a dark moment and I eventually shuffled out from beneath the pulp and sat there with my broken ski, hundreds of miles away from anyone in about -45 degrees and I just thought “this is ridiculous!”

I asked myself “what on earth am I doing here?” and it was only again sitting there reflecting on and going back to those original key messages of why I was doing it and eventually I sorted myself out, tentatively setting off again. That was quite a dark period on that trip.”

Tell us a little about your new book…

“It’s taken 18 months so its been quite a long project. I didn’t realise how hard writing a book was going to be. Finally, on June 11 we got the book “Endurance” out and it covers everything from my childhood and explains my background, my early fascination with Polar adventurers, Antarctica and why I have been doing this stuff. It stretches onto joining the Marines, a little bit on my time in the SAS, obviously without revealing anything sensitive at all, but the main focus of the book is about these major Polar expeditions. It covers in detail, three major trips in Antarctica and the crossing of Greenland as well with a group of civilian friends and hopefully people will enjoy the whys and the reasons behind what I have done. I’ve had lots of great feedback so far and the book is doing really well.

It is nice to get the story out there and if it motivates one or two other people to go and pursue their dreams then great. It doesn’t have to be doing anything as extreme as skiing to the South Pole, it can be a challenge of any kind. I think lately the book highlights with the right dogged determination and perseverance, no matter how crazy or insurmountable, whatever you want to do, if you keep chipping away at it and if you are passionate about it, then you will get there.”

Finally, what advice would you give to those going through resettlement and looking to get into extreme sports and expeditions…

“I would say really plan in advance. I planned for joining the Marines on what you would get in basic training and I think you need to apply the same principles to resettlement and think of what you want to do next.

So really plan ahead, use the resettlement process, it’s a brilliant scheme and just decide what your priorities are. For me it was job satisfaction and picking a job I know I would be happy doing. I always said that in the Army, that I would carry on serving if I was happy.

Figure out what is important to you, use the process to get the skills and qualifications that are going to help you. Once you decide what it is you want to do then be really determined about it and go for it!

That transition process (from military to civilian) is a huge change in your life so the more you can do to prepare for it then hopefully, the more seamless it is going to be.”

A case then of the old military adage of “Prior Preparation Prevents Poor Performance” applies to both Polar expeditions and military resettlement.

Louis Rudd was talking to Mal Robinson.

Louis Rudd Endurance : SAS Soldier. Polar Adventurer. Decorated Leader is out now.